Or, why you should listen to your English teacher

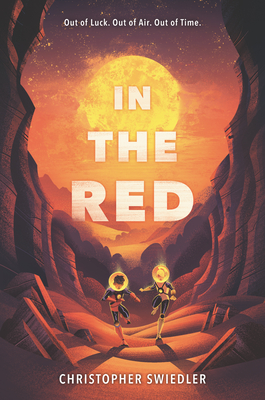

Early in the morning, when my kids are asleep, I’m a writer of science-fiction novels for middle-grade readers. My first book, IN THE RED, will be out on March 24 from HarperCollins. It’s the story of two kids living on Mars who get stranded during a solar flare and have to find their way back home.

Once the sun is in the sky, though, I’m an engineering manager at Roblox, which is a platform for middle-grade kids to make their own video games and play each other’s games. (If you’ve never heard of Roblox, ask a ten-year-old; after they roll their eyes at you, they’ll explain in great detail). One surprising thing I’ve learned after over a decade of working in the video game industry is that writing a novel and designing a game are pretty similar activities that require a lot of the same skills.

Don’t believe me? Read on…

Setting

Any video game has a setting: think of the strange world of bricks, turtles, and walking mushrooms from Super Mario Brothers, or the kooky science-fiction universe of Overwatch. Similarly, a big part of writing fantasy or science fiction is coming up with an imaginative setting. In both cases, the goal is to transport the audience to a different world—one that feels strange but somewhat familiar, exciting and yet in some ways predictable, and vivid but also believable.

IN THE RED takes place on Mars in the twenty-second century, when life there is normal enough that kids grow up there not knowing anything about what it’s like to live on Earth. As I was coming up with the story, I spent a lot of time daydreaming about what life would be like for those kids. I imagined that while early colonists would probably have lived underground for protection from solar radiation, eventually people would create large domed cities with shops, neighborhoods, schools, and parks. Everything inside the domes would feel pretty normal.

Except, of course, that it’s not normal at all. After all, you’re on Mars, which means that as soon as you leave the dome you have to deal with a deadly atmosphere, harsh solar radiation, and temperatures colder than Antarctica. And that’s all on a good day!

That intriguing world where inside is perfectly safe, outside is OMG YOU’RE TOTALLY GOING TO DIE planted some of the seeds that eventually became the idea for the novel.

Rules

Ah, rules. Kids hate them, don’t they?

Except, as every parent knows, there are no rules, your kids will be more bored than ever. Sometimes my kids spend more time making up the rules for their games than they actually spend playing them: “Okay, you’re totally dead if two nerf bullets hit your torso or one hits your head, but you’re just wounded if a sword hits you, except if you’re touching one of these three bases, and no close-range shots because they hurt, and also…”

Video game designers devote a lot of time to the rules of their games. In a sense, all gameplay is rules. Do this and you succeed. Do this other thing, and you fail. One of the fun things about games is that the rules can be extremely arbitrary and imaginative. Why does eating fruit make Pac-Man invincible? Dunno, but it’s fun!

Rules are the core of world-building for novels, too. They define what the characters can and can’t accomplish. The rules of THE HOBBIT dictate that Gandalf has many powers. But the rules also say that he’s not capable of just teleporting everyone to the Lonely Mountain, because otherwise the book would be about four pages long. Trolls are dangerous at night, but if you keep them out until the sun rises, they turn to stone. Bilbo is a master burglar, but even with his magic ring, Smaug the dragon can smell him.

With middle-grade and young-adult novels in particular, the rules are heavily shaped by parents and society. Stories for preteens usually involve bending rules that are well-meaning but flawed: CHARLOTTE’S WEB is about persuading the adult world that Wilbur deserves to live. Books for older teenagers are often about taking those stupid rules, throwing them in the trash, and then blowing up the trash can for good measure. The characters in THE HUNGER GAMES break every one of the rules of that world, and we cheer them on the entire time.

Part of the storyline for IN THE RED deals with kids going out onto the surface of Mars, where you can be killed by a hundred different things. When I started writing, I wondered what the rules for that sort of world would be. In California we require you to be sixteen years old and pass an exam before you can drive a car. Maybe there would be something similar for kids of Mars, where they have to demonstrate that they know how to operate a space suit? That was an intriguing thought. What would kids think of an exam like that? How would they feel about passing or failing?

And what about parents on Mars? Do they set their own rules for their kids? (surely.) Do kids hate those rules and bend them any chance they get? (yes!) Do they sometimes go outside onto the surface in the middle of the night, just for the thrill of sneaking out? (they’re kids, aren’t they?)

Answering these questions helped add the details that made the setting for IN THE RED something that middle-grade readers could connect with.

Character

One of the most fun things about video games is that you get to step into the shoes of a character: a sword-wielding ninja, a star quarterback, or a frenetic hedgehog. In a sense, every video game is written in the second person, where you are the hero or heroine.

Even though modern video games can show you that ninja in high-definition detail, there’s still an element of belief. You need to connect with that character in some way. The character needs to feel powerful in some way, or else it won’t feel possible to win the game. On the other hand, the character needs to be vulnerable, or else there’s no way to lose the game. On top of all of that, they need to be sympathetic and admirable, or else why would you want to be them?

Books usually aren’t written in the second person. Instead, they let a narrator or the protagonist themselves tell you what is happening. But if the story doesn’t connect the reader with that character, then no matter how whiz-bang the special effects plot and description, the reader isn’t going to be reading that book for long.

In particular, the main character needs to have something called agency, which is the power to affect the story through their actions. Can you imagine how boring it would be to read a book where the plot unfolds regardless of the choices the characters make? In STAR WARS, Luke Skywalker is recruited by Obi-Wan Kenobi, but he has to make his own choice to leave Tattoine. If he were dragged across the galaxy whining about power converters, nobody would care about him at all.

Video games are great at agency. They are agency machines. Absolutely nothing happens unless the player does something. Writers have to worry about making sure characters make choices; game designers have the luxury of knowing that agency is built into the concept of video games.

IN THE RED focuses on a boy named Michael who has something called environment suit anxiety disorder, which means that he has a panic attack any time he puts on a helmet and goes out onto the surface. Now, if I were living on Mars with that condition, I’d just stay inside where it’s safe. But of course, Michael isn’t satisfied with staying inside. He isn’t satisfied with his diagnosis. He feels something is definitely wrong, but whatever it is, it’s not with him.

He takes the environment suit test even though his parents have forbidden it. He sneaks outside with his best friend at night. They drive hundreds of miles in the middle of the night to see his father, even though there’s a powerful solar storm going on. These choices are his, and they drive the story forward.

Of course, just because they’re his choices doesn’t mean they’re good ones—which goes to show that kids should always listen to their parents unless they want to unwittingly embark on life-or-death adventures.

Risks

The motto of NASA Mission Control during the Apollo Moon landings was “failure is not an option.” It’s a great quote that sums up how much they were willing to do anything to make the missions successful.

But of course, if failure weren’t an option, then they wouldn’t need that motto. There was a huge risk of failure, and which is exactly why they invested massive amounts of time in preparation, planning, and redundancy. The possibility of losing the astronauts of the Apollo 13 mission is why the story of their return is so good.

All novels have the possibility—the likelihood—of failure. Think of any gripping story and evaluate the hero or heroine’s chances of success. One in ten? One in a hundred? One in a thousand? Or, like one of the pilots in STAR WARS says about getting a proton torpedo into the ventilation shaft of the Death Star, one in a million?

Furthermore, the consequences of failure in any story need to be devastating. If heroes and heroines fail, bad things happen. People die, or the bank reposesses their farm, or they lose their best friend and get laughed at by the entire school and they spend the night of the big dance at home playing Jenga with bad-breath Aunt Marge. Whatever it is that might happen, the protagonist of the story cares deeply about it not happening. They tell themselves that failure is not an option, and we silently cheer them on.

This isn’t to say that characters don’t suffer failures and setbacks. Readers don’t want to see a nice clean journey without any roadbumps. Smaller failures raise the stakes and add to the difficulty. Any time the characters in a movie have a plan to solve their problem after only thirty minutes, you know that plan is going to fail.

As anyone who has watched me play Madden on my kids’ XBox can attest, failure is a huge part of video games. It’s built into the system. You start out unable to meet even the smallest challenge. You fail over and over, until your skills start to improve. Then the game gets harder and you fail some more. The risk is always there. Why would you play a game that didn’t have the risk of failure?

Video game designers know all of this because they learned it from writers.

Michael, the main character of IN THE RED, begins by feeling the emotional risk of being rejected and ostracized because his panic attacks prevent him from going out onto the surface. His choices in the story lead to more risks. By choosing to sneak out, he takes the known risk that he might end up grounded till he’s thirty years old. But he also runs into the unknown risks of Mars itself. A massive solar flare knocks out all of the planet’s communication and navigation satellites and Michael and Lilith end up stranded out on the surface. They can’t go out onto the surface during the day for more than a few minutes without being killed by radiation. As they try to find their way back, more risks emerge: collapsing glaciers, man-made volcanoes, dust storms. If it weren’t for the risks (both emotional and physical), there literally wouldn’t be a story to tell.

Pacing

We all need excitement in our lives. But we also need down time. We need rest; we need moments with our families and friends; we need time to reflect.

Game designers know this very well. No game sets a single pace and keeps it throughout. They’re always broken up into levels and missions that give the player some quiet time to take a breath before heading out into the excitement again.

And where did game designers get this idea? From writers. Friends, writers invented pacing. Thousands of years ago, when we first gathered around campfires, the first storytellers taught themselves how to pace their stories. Beowulf, the Odyssey, and other epics enshrined patterns for structure and pacing. Heroes and heroines venture out—they suffer setbacks—they regroup—and they journey again.

HARRY POTTER AND THE SORCERER’S STONE is a good example. The book contains a series of exciting encounters: a fight with a troll, a Quiddich match, a visit to the Forbidding Forest. But each of these is separated by quieter scenes where Harry and his friends are given the time to process the crazy things that are happening.

Can you imagine if those quieter scenes weren’t there? Would the book be anywhere near as good if it were jam-packed with TROLLS WIZARDS DRAGONS CENTAURS VOLDEMORT GO GO GO GO…?

I had to be very conscious of pacing with IN THE RED. When Michael and Lilith arrive at his father’s research station, they find it mysteriously abandoned. As they try to figure out what has happened there, the two of them have a little time to feel the emotions that all of the risks have brought on. This gives the reader time to pause and regroup as the story builds up again. And then, of course, Michael and Lilith discover the reason everyone has fled the station. (Spoiler alert: it’s not good.)

Video games are the same way. Pick any single-player game and you’ll see small challenges that lead to big challenges that lead to a final confrontation. Even positively ancient video games like Pac Man, Galaga, and Donkey Kong do this: they apply some pressure, they increase the risk, and then they give you a chance to rest for a moment before throwing you back into more challenges.

That’s pacing.

Conclusion

So far none of my kids has said to me that they want to be a writer when they grow up. That’s fine—I’ll be happy and proud of them no matter what they do. But they do tell me, quite often, that they think they’d like to design video games. In response, I nod sagely and give them a supportive hug.

And then I hand them a book to read.

Christopher Swiedler is an author and software engineer who lives with his wife and three children in California, where they’re under constant threat from earthquakes, tsunamis, and the occasional Martian dust storm. His goal in life is to win the Newbery Honor (not the medal itself) because he believes being a runner-up builds good character. He is represented by Bridget Smith of JABberwocky Literary Agency. His debut novel, IN THE RED, will be published by HarperCollins in March 2020. He can be found at https://christopherswiedler.com

I loove how fun and enlightening this was to read, being both a book and a video game nerd, you touched me right in the being, and you definitely stirred the right side of my brain, thank you!

LikeLike